J.ophthalmol.(Ukraine).2021;1:76-80.

|

http://doi.org/10.31288/oftalmolzh202117680 Received: 03 June 2020; Published on-line: 12 February 2021 A case of endophthalmitis associated with gonococcal sepsis T. A. Krasnovid 1, I. V. Svystunov 2, O. S. Sidak-Petretskaia 1, N. I. Bondar ¹ 1 SI "The Filatov Institute of Eye Diseases and Tissue Therapy of the National Academy of Medical Sciences of Ukraine"; Odesa (Ukraine) 2 Shupyk National Medical Academy of Postgraduate Education; Kyiv (Ukraine) TO CITE THIS ARTICLE: Krasnovid TA, Svystunov IV, Sidak-Petretskaia OS, Bondar NI. A case of endophthalmitis associated with gonococcal sepsis. J.ophthalmol.(Ukraine).2021;1:76-80. http://doi.org/10.31288/oftalmolzh202117680 Background: Gonococcal ocular lesions develop most commonly due to poor hygiene habits, when the infection is transmitted by eye-hand contact; in addition, they may develop when the infection is transported to the eye as a result of hematogenous or lymphogenous spread. Purpose: To present a rare case of endophthalmitis secondary to gonococcal sepsis, and to highlight its clinical features. Material and Methods: Visual acuity assessment, comprehensive eye examination, and microbiological examination. Results: Patient’s history was significant for acute suppurative gonococcal prostatitis (with acute retention of urine, and severe sepsis with liver abscess, and suppurative tonsillitis), for which he had been treated as an in-patient at the Department of Urology of the city hospital. In addition, he had suppurative blepharitis of the left eye. A week after he was discharged from the Department of Urology, he was hospitalized to the Department of Ocular Trauma of the Filatov institute with the diagnosis of endophthalmitis in the left eye. The patient poorly responded to treatment, and clinical manifestations of endophthalmitis were becoming more and more severe. He underwent evisceration of the left eye. Conclusion: Consultations of allied health professionals and multiprofessional management of gonorrhea patients are required to prevent complications in various organs and systems, should gonococcal sepsis develop. Keywords: gonococcal infection, sepsis, endophthalmitis, evisceration

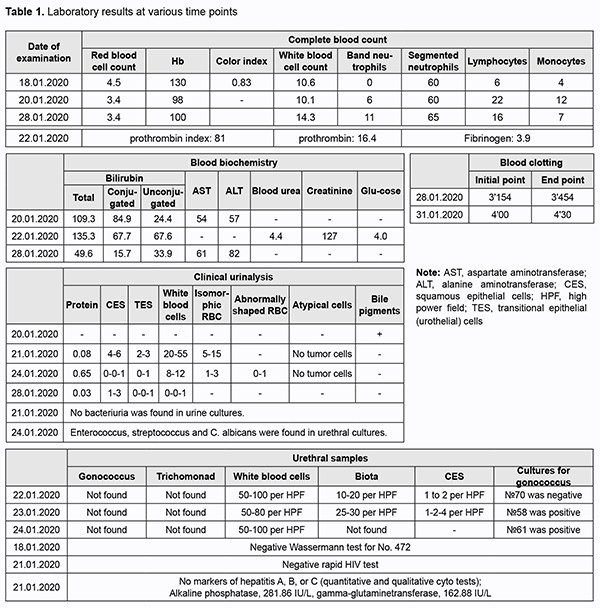

Gonorrhea, a human infectious disease that may be acute or chronic, is mostly sexually transmitted, causes inflammation commonly within urogenital mucous membranes, and is manifested by secretions. Galen, a Greek physician (AD 130-200), is credited with naming gonorrhea after gonos (semen) and rhoia (to flow), but the disease had been known much earlier. Neisser first observed the causative agent, gonococcus, in stained smears of vaginal, urethral and conjunctival exudates in 1879. N. gonorrhoeae belongs to the family Neisseriaceae (Bergey's 1997), and is a member of the genus Neisseria. There are an estimated 86.9 million gonorrhea infections occurring each year [1]. Gonococci can affect also mucous membranes of the rectus, eye and pharynx; they rarely cause generalized infection and marked intoxication [2, 3]. Extragenital N. gonorrhoeae infections can be divided into conjunctivitis, infections of the mouth and pharynx (stomatitis, gingivitis, pharyngitis and laryngitis), disseminated gonococcal infection (bacteriemia, conjunctivitis, iridocyclitis, dermatitis, myositis, meningitis, pleurisy, arthritis, synovitis, and osteomyelitis), and acute gonococcal perihepatitis [3]. Disseminated gonococcal infection (DGI) is very rare, affecting 0.1-0.3% of patients with gonorrhea, and can occur as a result of metastasis from the site of primary infection. DGI has been reported to have a female predominance, with a female to male ratio of 4:1, and is especially frequent in pregnancy. It is manifested clinically by fever, tenosynovitis (asymmetric, involving hands and feet), arthritis, hepatitis, mild myopericarditis, and rash, most commonly, on the distal extensor surfaces of the limbs [2, 4]. Disseminated gonococcal infection may be complicated by the development of gonococcal sepsis, which is sometimes accompanied by endo-, myo-, and pericarditis, meningitis, brain abscess, peritonitis, osteomyelitis, synovitis, with lesions of the liver and kidneys, and these disorders have no pathognomonic symptoms. Most commonly, general condition is moderately severe, with intermittent fever (38-40.5°С), chill, joint pain, and skin lesions. A diagnosis of DGI is confirmed by blood cultures [2]. The course of gonococcal sepsis is variable, like for all types of septicemia [5]. There is no difference in clinical picture or disease course between gonococcal septicopyemia and any other pyaemia, but the former is less resistant to antibiotics, and advances in antibiotics have improved treatment outcomes of gonococcal septicopyemia. Bacterial endocarditis secondary to infection caused by N. gonorrhoeae was the leading cause of infectious endocarditis prior to the antibiotic era, accounting for up to 26% of all cases. During the period after the introduction of penicillin in 1942 and until 1979, there were only 11 culture-proven cases of gonococcal endocarditis in the English literature. A more common type of gonopyemia is a mild form with intermittent fever (38-39 °С), chill, arthralgia or arthritis and typical skin rash. This form of septicemia has been called “benign gonococcemia” or “gonococcal dermatitis syndrome”. However, whether even the mildest form of septicemia is really benign is a question. It has been noted that all types of gonococcal sepsis can be commonly well treated by antibiotics, if appropriate therapy is initiated before irreversible changes develop in the organs. Therefore, the clinical continuum of gonococcal lesions ranges from as mild as asymptomatic infection of mucous membranes to as severe as purulent meningitis and gonococcal sepsis. To the best of our knowledge, in recent years, there have been no reports of fatal cases of gonococcal sepsis. In addition, cases of gonococcal septicemia with the development of suppurative and metastatic foci of infection, endocarditis and meningitis have been rarely reported, and cases of gonococcal septicemia associated with Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome have been extremely rarely reported [6]. ICD-10 A54.8 code (“Other gonococcal infections”) includes gonococcal: brain abscess, endocarditis, meningitis, myocarditis, pericarditis, pneumonia, sepsis and skin lesions; these infections should be also taken into account. Moreover, ICD-10 A54.3 code (“Gonococcal infection of eye”) includes gonococcal: conjunctivitis, iridocyclitis and ophthalmia neonatorum due to gonococcus. Gonococcal ocular lesions develop most commonly due to poor hygiene habits, when the infection is transmitted by eye-hand contact [2]; in addition, they may develop when the infection is transported to the eye as a result of hematogenous or lymphogenous spread. The pathogen may affect the neonatal eye either as a result of transplacental passage of the pathogen to the fetus or during passage of the fetus through the birth canal. The incubation period of gonococcal infection generally ranges from 3 to 19 days [7]. On examination, there are marked lid edema, photophobia and copious purulent discharge in the eye corners. The conjunctiva is markedly hyperemic, and mild conjunctival hemorrhage is observed. Gonococcal conjunctivitis may have an asymptomatic course as well. In more severe disease, the cornea is involved, and isolated perforated corneal ulcers develop. Progression of this process may result in ulcerous destruction of the cornea and panophthalmitis, leading to blindness. The purpose of this work is to present a rare case of endophthalmitis secondary to gonococcal sepsis, and to highlight its clinical features. A male patient born in 1975 was under supervision at the Department of Ocular Trauma of the Filatov institute. On January 18, 2020, he was taken by the emergency team to the Department of Urology of the city hospital, where he was diagnosed with acute suppurative gonococcal prostatitis (and retention of urine, severe sepsis with liver abscess, suppurative blepharitis of the left eye, and suppurative tonsillitis) and stayed until February 4, 2020. On admission to the hospital, he complained of urinary retention, purulent urethral discharge, general weakness, heavy breathing and shortness of breath. He reported that he had been ill over two months, but his condition worsened and body temperature rose to 39 °С 5 days before admission. On examination performed on admission to the hospital, his general condition was satisfactory. The skin surface and the visible mucous membranes were of normal color and clear and respiration was vesicular. In addition, blood pressure was 140/80 mmHg, heart rate 78 bpm and body temperature 36.6°C. Heart tones were muffled, with a regular rhythm. The tongue was wet and clear. Abdomen was tender and there was painful suprapubic palpation. The liver and kidneys were not palpable. No signs of peritoneal irritation were observed. No costrovertebral angle tenderness at both sides. On January 18, 2020, at the admission room, he received a catheter due to acute retention of urine, and 500 ml of urine was drawn off by the catheter. On the same day, the patent had a cancer examination. The skin surface was clear, peripheral lymph nodes not enlarged, and the thyroid gland was unremarkable. Rectal examination revealed an enlarged prostate with a mobile rectal mucous membrane over it. Gonococci were found in urethral smears. On January 19, 2020, urinary tract ultrasound was performed. The bladder volume was 180 mL, and prostate dimensions and volume, 3.4×5.8×4.8 cm and 49 cm3, respectively. The patient was diagnosed with exacerbation of chronic pyelonephritis, dysmetabolic nephropathy, urolithiasis, and acute prostatitis. On January 20, 2020, abdominal ultrasound was performed, showed a multilocular cyst in the right lobe of the liver, and the patient was diagnosed with hepatomegaly and chronic pancreatitis. In addition, a chest X-ray was unremarkable. Moreover, the patient underwent a trocar cystostomy. On January 21, 2020, he was consulted by a therapist and an infectious disease doctor and was diagnosed with active hepatitis of unknown etiology. On January 24, 2020, another abdominal urinary tract ultrasound was performed. The bladder volume was 270 mL, and prostate dimensions and volume, 3.4×5.3×4.8 cm and 49.9 cm3, respectively. The patient was diagnosed with diffuse focal changes in the prostate and acute prostatitis. On January 24 and 25, 2020, chest X-ray and pleural ultrasound were performed, and bilateral hydrothorax was found. On January 28, 2020, the patient was consulted by a surgeon and was diagnosed with severe sepsis with involvement of the liver (abscess) and left eye (suppurative blepharitis), and suppurative tonsillitis. On January 31 and February 4, 2020, he was consulted by a skin and sexually transmitted disease (STD) specialist, and was diagnosed with chronic gonorrhea and gonococcal prostatitis (A54.2). On February 1, 2020, the patient underwent liver abscess drainage. On February 3, 2020, he underwent a suprapubic cystostomy. Table 1 shows changes in laboratory results over time.

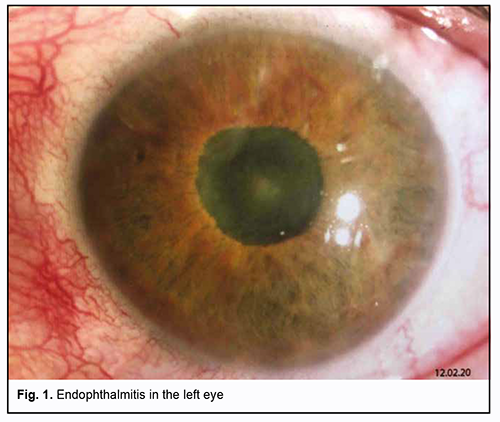

The patient received conservative treatment, including Ceftriaxone, Gepacef combi, Ringer’s saline, Izosol (infusion solution), Medrolgin (injection solution), Hepametion (injection solution), Omnic, Canephron N, Cycloferon, Omez, Pancreatine, Enterol, Enterosgel, Enterogermina, Fluconazole, Nystatin, tivortin aspartate, maxibalance, Dicloberl suppositories, levofloxacin 0.5% ophthalmic solution (Oftaquix), and 30% ophthalmic solution (albucide). This treatment produced positive changes across a number of markers, and voluntary and painless urination with adequate urine output was restored. The skin surface and the visible mucous membranes were of normal color. There was no discharge through the drainage tube from the liver abscess. There was no pus discharge from the urethra. The patient could breathe freely through his nose and had no shortness of breath. There was, however, no vision in his left eye. On February 3, 2020 (at day 17 after admission), he was discharged from the hospital to be treated as an outpatient by a local surgeon and a local skin and STD specialist, and referred to an ophthalmologist for making a decision on his eye treatment. On February 10, 2020, the patient presented to the Filatov institute and complained of no vision, redness and photophobia in his left eye for the last 4 days. At the same day, he was admitted as an in-patient to the Department of Ocular Trauma and diagnosed with endophthalmitis in the left eye (Fig. 1).

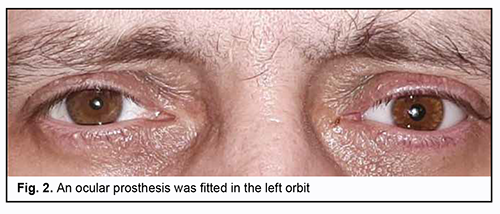

The left eye looked inflamed with mixed conjunctival injection. Other objective examination findings in the left eye included a clear cornea; moderately shallow and clear anterior chamber; abnormal iris color; circular posterior synechia; rigid pupil; lens haze; anterior lens capsule vascularity; and dim reflex. The right eye was quiescent. Other objective examination findings in the right eye included a clear and bright cornea; moderately shallow and clear anterior chamber; clear lens; pink reflex; pale pink optic disc with clear margins; and attached retina. Patient’s visual acuity was 0 OS and 1.0 OD. In addition, intraocular pressure (IOP) measured by pneumotometry was 14.0 mmHg (with treatment by dorzotymol plus Brimonal 0.2% twice daily) OS, and IOP measured by palpation was normal OD. On February 10, 2020, important ocular ultrasound findings included severe preretinal vitreous fibrosis, chorioretinal edema (suspected ciliary body and choroidal detachment), optic disc cupping and attached retina in the left eye. On February 12, 2020, the patient underwent evisceration of the left eye. The patient’s postoperative period was unremarkable. On February 13, 2020, there was microbiologic evidence of Escherichiae coli in the anterior chamber samples. The patient received conservative treatment, including Azithromycin, 500 mg daily; Levofloxacin, 500 mg daily; Omnic, 400 mg daily; Melbek, 15 mg i/m; Dexalgin, 25 mg i/m; Dorzotymol ophthalmic solution; Brimonal ophthalmic solution 0.2%; Vigamox ophthalmic solution 0.5%; Okomystin ophthalmic solution 0.01%; Oftaquix ophthalmic solution 0.5%; Uniclophen ophthalmic solution 0.1%; and Floxal ophthalmic ointment. A week after surgery, in the left eye, the conjunctival cavity was clear, and conjunctival sutures were clear, there was no edema, and the stump was movable in all directions. An ocular prosthesis was fitted in the orbit (Fig. 2). There was no bacterial growth in conjunctival samples.

Conclusion We presented a rare case of disseminated gonococcal infection complicated by severe sepsis with liver abscess, suppurative tonsillitis, and suppurative blepharitis of the left eye leading to endopthalmitis, with subsequent evisceration. Gonococcal ocular lesions are associated with late presentation to the ophthalmologist, fast endophthalmitis development, and asymmetric involvement, but no corneal involvement. Consultations of allied health professionals and multiprofessional management of gonorrhea patients are required to prevent complications in various organs and systems should gonococcal sepsis develop.

References 1.Rowley J. Hoorn SV, Korenromp E, et al. Chlamydia, gonorrhea, trichomoniasis and syphilis: global prevalence and incidence estimates. Bull World Health Organ. 2019 Aug 1;97(8):548-62. 2.Molochkov VA, Ivanov OI, Chebotariov VV (eds). [Sexually transmitted infections: Clinical features, diagnosis and treatment]. Moscow: JSC Meditsina Publishing House; 2006. p.356-70. Russian. 3.Skripkin IuK, Mordovtsev VN (eds). [Skin and venereal diseases: A guide for physicians. Two volumes]. 2nd edn (revised). Vol. 1. Moscow: Meditsina; 1999. p.608-29. Russian. 4.Levens E. Disseminated gonococcal infection. Prim Care Update Ob Gyns. 2003;10(5):217–9. 5.Shaposhnikov OK, editor. [Venereal diseases: A guide for physicians]. 2nd edn (revised). Moscow: Meditsina; 1991. p.350-1. Russian. 6.Wolff K, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, et al (eds). Potekaieva NN, Lvova AN (transl. eds). [Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine]. Vol. 3. Moscow: Binom; 1991. p.2173. Russian.

The authors declare no conflict of interest which could influence their opinions on the subject or the materials presented in the manuscript.

|