J.ophthalmol.(Ukraine).2019;1:61-64.

|

http://doi.org/10.31288/oftalmolzh201916164 Received: 24 December 2018; Published on-line: 28 February 2018 Combined Treatment for Recurrent Herpetic Stromal Keratitis with Ulceration: a Case Report L.F. Troychenko, Cand. Med. Sc; T.B. Gaydamaka, Dr. Med. Sc.; G.I. Drozhzhyna, Dr. Med. Sc., Prof. Filatov Institute of Eye Diseases and Tissue Therapy, NAMS of Ukraine; Odessa (Ukraine) E-mail: tlf2008@ukr.net TO CITE THIS ARTICLE: Troychenko LF, Gaydamaka TB, Drozhzhyna GI. Combined Treatment for Recurrent Herpetic Stromal Keratitis with Ulceration: a Case Report. J.ophthalmol.(Ukraine).2019;1:61-4.http://doi.org/10.31288/oftalmolzh201916164

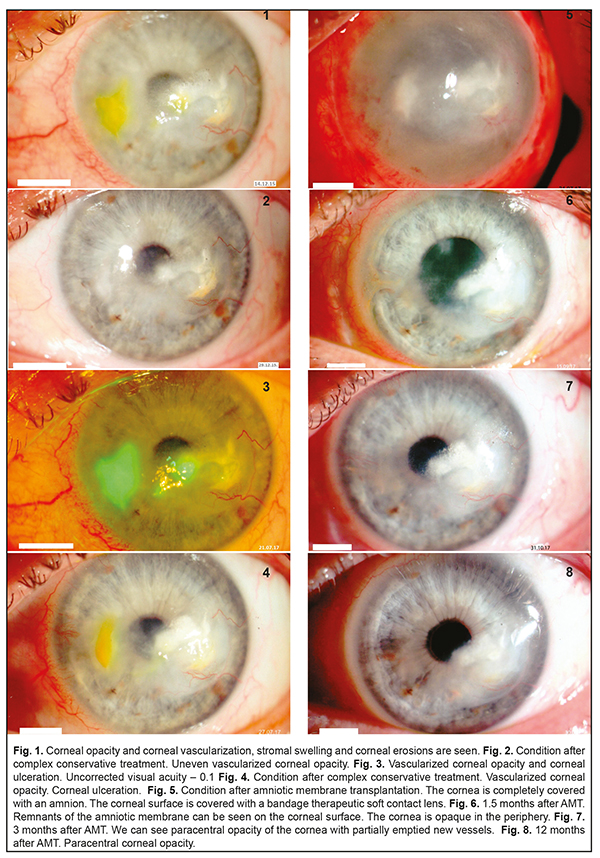

Herpes simplex keratitis (HSK) is a severe ophthalmic pathology which comprises 20-50% of inflammatory diseases in the cornea. Since keratitis is characterized by a long-term duration, severity, and a tendency to recurrence, studies on ophthalmic herpes and searches for new treatments are of great relevance. Our clinical case demonstrated successful combined treatment of a recurrent stromal herpetic corneal lesion with ulceration. Both treatments, conservative (complex etiotropic, anti-viral, anti-inflammatory, and nutrition-improving) and surgical (an onlay technique), were successful. At 12 months after surgery, the patients had no pain syndrome; the corneal surface was epithelialized. No recurrence of herpetic keratitis was observed. Thus, a combination of etiotropic pathogenic treatment and AM transplantation appears to be effective for severe long-lasting recurrent herpetic keratitis with the presence of defects on the corneal surface. Keywords: herpetic keratitis, treatment Herpes simplex keratitis (HSK) is a severe ophthalmic pathology and comprises 20-50% of in inflammatory diseases in the cornea [1]. Eyes are more frequently affected by Herpes simplex virus type 1. The primary lesion is characterized by pathologic processes on the corneal surface while stromal lesions are common for recurrent herpetic keratitis. HSK often occurs after acute respiratory viral infections (45.5%), traumatic injuries of the cornea (26.8%), stress (22.5%), and contact correction (3.4%) [2]. Since keratitis is characterized by a long-term duration, severity, and a tendency to recurrence, studying ophthalmic herpes and developing new treatments are of great relevance. Case History A 54-year-old patient D. had been followed up since 2015. The patient was diagnosed moderate dry eye syndrome and presbyopia in both eyes; corneal opacity with vascularization and recurrent herpetic stromal keratitis in the left eye. Prior to admission to the Filatov Institute, the patient had been experiencing the frequent recurrence of viral keratitis for 10 years (1-2 times a year). The patient had been treated at the place of residence; however, a full range of treatment, using etiotropic (anti-viral) and anti-inflammatory agents, had not been received. In 2015, the recurrence of keratitis became more frequent, to 3 times a year, and the patient sought medical treatment in the Corneal Pathology Department at the Filatov Institute. On admission, on December 12, 2015, deep vascularized opacity was noted in the optic and paracentral parts of the cornea in the affected eye. The fluorescein test showed corneal erosion (2/3 mm). Uncorrected visual acuity at admission was 0.2. The Schirmer test was 6.0 mm and the Norn’s test was 7 s (Fig. 1).

Microbiological testing of the conjunctiva discharge revealed no pathology. In addition to standard ophthalmic examinations, the patient underwent rheoophthalmography (ROG), rheoencephalography (REG), and immunogram to reveal sensitization to antigens of herpes. Pulse Volume according to the Rheographic Quotient (RQ) was decreased by 17% as compared to the fellow eye; tonic properties of the large vessels were increased by 28%, and blood flow velocity was decreased by 50%. The immunogram findings showed an increased level of lymphocytes, decreased levels of T-cells and natural killer cells. In addition, sensitization to antigens of herpes and cornea was noted. Anti-viral, etiotropic, anti-inflammatory, tear- substituting, and corneal nutrition-improving treatment made it possible to manage recurrent keratitis. The corneal surface epithelization was complete and the corneal surface was not stained by fluorescein. Visual acuity improved to 0.6 (Fig. 2). During one year and a half, till 2017, the patient received tear-substitute drugs, containing the hyaluronic acid, trehalose, and ectoin, which improved the corneal nutrition (antioxidants, vitamins, neuroprotectors). No recurrence of viral keratitis was noted. Visual acuity remained at the level of 0.5-0.6 within this period of time. In July 2017, after having an acute respiratory viral disease and severe stress, the patient’s condition deteriorated. Herpetic keratitis recurred with the presence of corneal ulceration and complicated by pain syndrome (Fig. 3). The microbiological testing of the conjunctiva discharge revealed staphylococcus epidermidis with a concentration of ˂ 10². Despite the etiotropic anti-viral and anti-inflammatory treatment, the patient’s condition improved insufficiently within 14 days. The corneal surface still had defects and active vascularization was noted in the periphery (Fig. 4). The patient was recommended a curative operation, transplantation of cryopreserved amniotic membrane using an overlay technique with AM sutured to episclera and conjunctival surface reconstruction, which was performed on July 27, 2017. After surgery, the corneal surface with AM was covered with a bandage therapeutic soft contact lens (Fig. 5). At Day 2, post-operatively, pain syndrome was managed; the patient continued the conservative etiotropic and anti-inflammatory treatment. At 1.5 Months after amniotic membrane transplantation (AMT), the amnion was partially resorbed on the corneal surface. Corneal epithelization was complete and the fluorescein test was negative. Visual acuity improved to 0.3 (Fig. 6). At 3 months after AMT, the complete resorption of the amnion and complete corneal epithelization were noted; the fluorescein test was negative. The vessels on the corneal surface were partially emptied. The Schirmer test and the Norn’s test increased to 10.0 mm to 12 s, respectively. Visual acuity improved to 0.5 (Fig. 7). Within 5 postoperative months, the patient underwent the system anti-viral and anti-inflammatory treatment and local instillations of antiseptics, recombinant human interferon, dexamethasone, vitamins, and preservative-free tear-substitute with trehalose. The immunology testing showed: improved immune reactivity of the body; increased to the normal ranges pulse blood volume (RQ); tonic properties of the small vessels decreased by 20%; blood flow velocity increased by 30%. Visual acuity was 0.5. Corneal epithelization, regressed vascularization, and decreased area of corneal opacity were noted at 12 months after AMT and a course of etiotropic anti-viral treatment. Visual acuity improved to 0.6 (Fig.8). At present, the patient is receiving tear-substitute treatment (preservative-free agents with trehalose), which improves corneal nutrition. Uncorrected visual acuity is 0.6. Discussion At the present time, treatment of herpetic ocular infection is a challenging task in ophthalmology. For treating herpetic diseases, there are numerous drugs which have etiotropic and immunocorrecting action depending on the etiology, pathology, and clinical symptoms. Antiherpetic drugs can be divided into three groups based on the mechanism of action: a chemotherapeutic agent, specific immune correctors, and non-specific immune correctors [2-6]. Antiherpetic drugs, which are used in ophthalmology as gel and ointment, are presented by acyclovir, an analogue of purine nucleoside blocking the viral DNA synthesis, and ganciclovir, a nucleoside and an analogue of guanine. One of the leading roles in the complex antiviral therapy belongs to new-generation interferon-inducing drugs (tilorone, oxodihydroacridinylacetate sodium, acridonacetic acid) which successfully combine etiotropic and immunocorrecting effects. The drugs induce the production of endogenous interferon by T and B lymphocytes, enterocytes, and hepatocytes [7]. Today, immune therapy for ophthalmic herpes includes specific (herpetic vaccine and herpetic immunoglobulin) and non-specific (interferons and interferon inductors, cytokines, micro-element vitamin complex, etc) methods. In addition, tear substitute drugs are used with the preference of preservative-free ones [8, 9]. To achieve the positive result of therapy, the duration of the complex antiviral therapy should be at least 4-6 months. All the drug groups above were used in the complex treatment for the patient described. The recurrence of herpetic keratitis and the formation of a long-lasting corneal defect require surgical treatment [10]. We draw our attention to amniotic membrane transplantation (AMT), one of the important recent techniques in ocular surface surgery [11]. Although AM was first performed in ophthalmology over 70 years ago, this is 1995 since when AMT has been widely used in patients and has shown good results [12]. Curative keratoplasty using an amnion or other long-term storage plastic materials has come into widespread acceptance [13-14]. The major indications to AMT for the reconstruction of the ocular surface are persistent corneal epithelial defects with ulceration of different etiology [15, 16]. Clinical studies have shown that AMT benefits epithelialization and differentiation of the ocular surface epithelium [15-18]. The most important growth factors for ocular surface wound healing, which are epidermal growth factor and keratinocyte growth factor, were mainly expressed in the amniotic epithelium but also in the stroma [17, 18]. There are several surgical AMT techniques. We used an onlay or patch technique. Classical indications for this technique vary from acute burn injuries to acute herpetic keratitis and severe Stevens-Johnson syndrome [14, 18, 19, 20]. This allows using wound healing and anti-inflammatory AM properties which are limited in time [18, 22]. In an onlay technique, a big portion of AM is placed on the ocular surface as a biological covering and sutured in the limbus or in the episclera [15]. In the case reported, AM successfully performed its anti-inflammatory and wound healing actions and was partially resorbed at 1.5 months. At 3 months after surgery, AM was completely resorbed, which was accompanied by corneal epithelium healing. In addition, new vessels were partially emptied. To conclude, the clinical case reported demonstrated successful combined treatment of a recurrent stromal herpetic corneal lesion with ulceration. A success was both complex conservative etiotropic, anti-viral, anti-inflammatory, and nutrition-improving treatment and surgical treatment using an onlay technique. At 12 months after surgery, the patients had no pain syndrome; the corneal surface was epithelialized. No recurrence of herpetic keratitis was observed. Thus, a combination of etiotropic pathogenic treatment and AM transplantation appears to be effective for severe long-lasting recurrent herpetic keratitis with the presence of defects on the corneal surface. References

1.Anina EI, Martoplyas KV. [Corneal Pathology among adult population in Ukraine]. [Proceedings of XII Ukrainian Congress of Ophthalmologists, 26-28 May 2010]. Odessa; 2010:5. Russian. 2.Kasparov AA. [Treatment of Herpes virus keratitis: 35 year experience]. [New technologies in treatment of corneal diseases: All-Russian Scientific Practical Conference with international participations, Fedorov Memorial Lectures, 25-26 June 2004: collection of papers]. M.;2004: 574-80. Russian. 3.Dembskii LK, Shirshova ON, Mironiuk OV. [Some aspects of organization of virus keratitis treatment]. [Surgical treatment and rehabilitation of patients with ophthalmic pathology: scientific and practical conference with international participation, 2004: proceedings]. K.; 2004: 99-100. Russian. 4.Kasparov AA. [Treatment of herpes virus keratitis. In: Current issues of herpes virus infections]. M.; 2004: 31-7. Russian. 5.Kasparov AA. [Modern methods for herpes virus keratitis]. [Scientific and Practical conference “Modern methods of diagnostics and treatment for cornea and sclera diseases”]. M.;2007:273-6. Russian. Современные методы лечения герпесвирусного кератита // Научно-практич. 6.Kaye S, Choudhary A. Herpes simplex keratitis. Progress in retinal and eye research. 2006;25(4):355 – 380. 7.Kovalchuk LV, Gankovskaya LV, Martirosova NI, Vasilenkova LV, Sokolova EV, Levchenko VA. [The approaches to immunocorrecting therapy in ophthalmology on position of new presentation about inherent immunity] Refraktsionnaia khirurgiia I oftalmologiia. 2008;1:44-8. Russian. 8.Pozdnyakov VI, Maichuk YuF, Pozdnyakova VV. [Algorithm of a therapy for severe ophthalmic herpes]. [Current issues of inflammatory eye diseases: scientific and practical conference, 20-21 November, 2001: proceedings]. M.;2001:151-3. Russian. 9.Kasparov AA. [Modern methods of treatment for severe infectious diseases of the cornea]. [IX Congress of Ophthalmologists of Russia, 16-18 June 2010: proceedings]. M.; 2010:296-8. Russian. 10.Gaydamaka TB. [Antirelapse treatment of the patients with herpetic keratites]. Oftalmol Zh. 2009;5:6-9. Russian. 11.Sereda EV, Drozhzhina GI, Gaidamaka TB, Ivanovskaia EV, Ostashevskii VL, Ivanova ON, Kogan BM. [Efficacy of different amniotic membrane transplantation techniques in patients with inflammatory and degenerative pathology of the cornea]. Oftalmol Zh. 2016;4:3-10. Russian. 12.Kim JC, Tseng SC. Transplantation of preserved human amniotic membrane for surface reconstruction in severely damaged rabbit corneas. Cornea. 1995;14:473–84. 13.Trufanov SV. [The use of preserved human amniotic membrane in reconstructive surgery of the eye]. Author’s thesis for Cand. Med. Sc. M.:2004. 24p. Russian. 14.Fedorova EA. [The use of lyophilized amniotic membrane in treatment of inflammatory corneal diseases]. Author’s thesis for Cand. Med. Sc. M.:2004. 24p. Russian. 15.Seitz B. Amniotic membrane transplantation. An indispensable therapy option for persistent corneal epithelial defects. Ophthalmologe. 2007;104:1075–9. 16.Shortt AJ, Secker GA, Notara MD et al. Transplantation of ex vivo cultured limbal epithelial stem cells: a review of techniques and clinical results. Surv Ophthalmol. 2007;52:483–502. 17.Koizumi NJ, Inatomi TJ, Sotozono CJ, Fullwood NJ, Quantock AJ, Kinoshita S. Growth factor mRNA and protein in preserved human amniotic membrane. Curr Eye Res. 2000;20:173–7. 18.Tseng SC, Espana EM, Kawakita T et al. How does amniotic membrane work? Ocul Surf. 2004;2:177–87. 19.Sippel KC, Ma JJ, Foster CS. Amniotic membrane surgery. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2001;12:269–81. 20.Ueta M, Kweon MN, Sano Y et al. Immunosuppressive properties of human amniotic membrane for mixed lymphocyte reaction. Clinical and Experimental Immunology. 2002;129:464–70. 21.Kheirkhah A, Johnson DA, Paranjpe DR, Raju VK, Casas V, Tseng SC. Temporary sutureless amniotic membrane patch for acute alkaline burns. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126:1059–66. 22.Thomasen H, Pauklin M, Steuhl KP, Meller D. Comparison of cryopreserved and air-dried human amniotic membrane for ophthalmologic applications. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2009;247:1691–700.

|