J.ophthalmol.(Ukraine).2016;2:3-8.

|

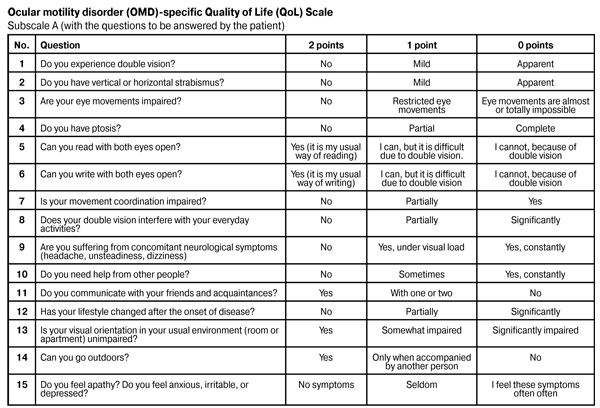

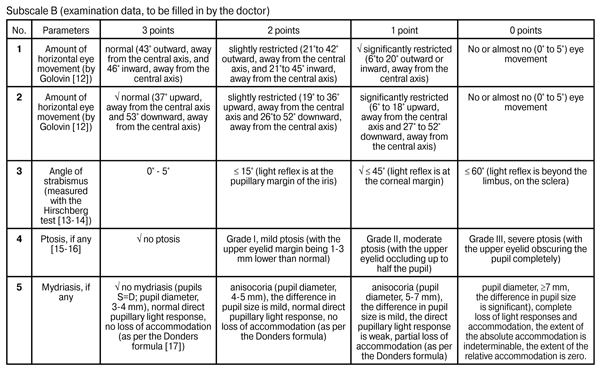

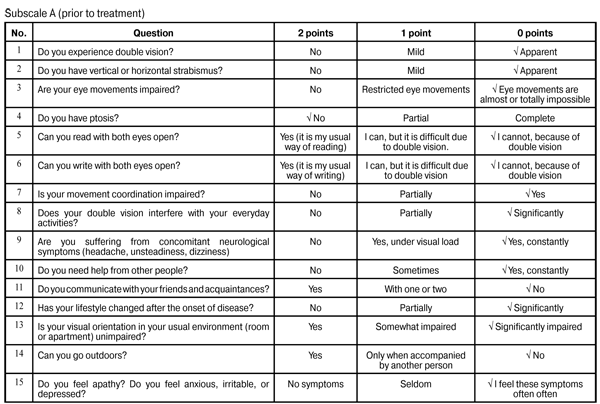

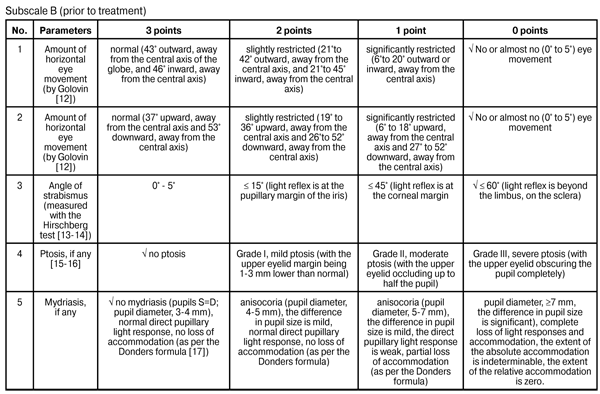

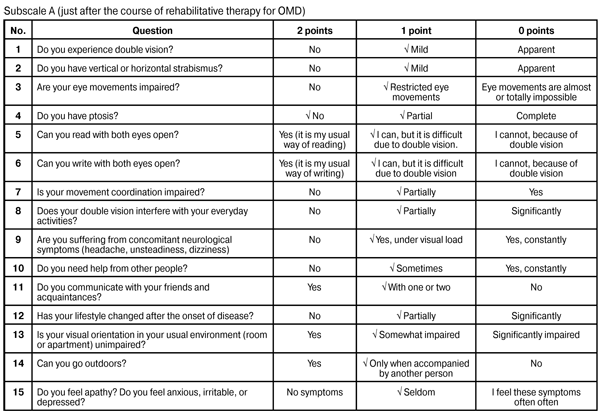

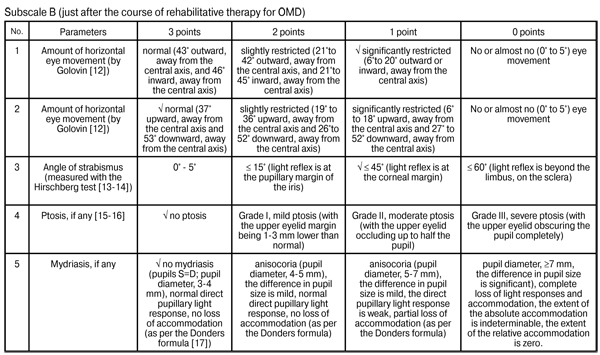

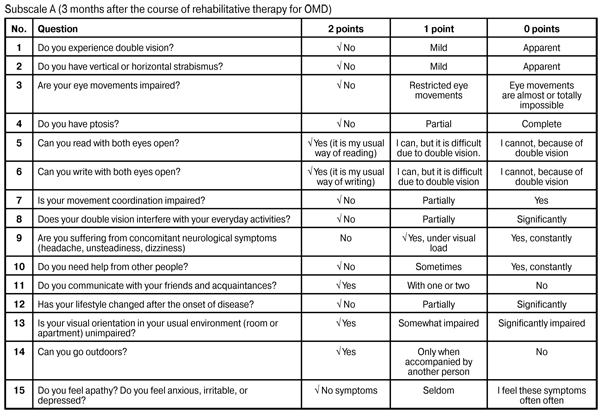

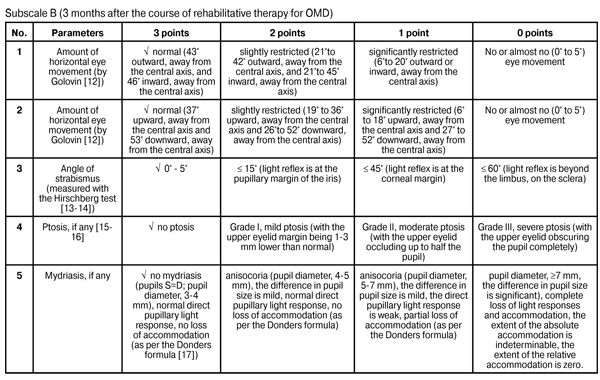

https://doi.org/10.31288/oftalmolzh2016238 Potential of the quality of life (QoL) tool for patient profiling in paralytical strabismus V.M. Zhdanova, Cand Sc (Med) L.V. Zadoianyi, Cand Sc (Med) V.A. Vasiuta, Cand Sc (Med) K.S. Ehorova, MD Romodanov Neurosurgery Institute, National Academy of Medical Science Kyiv, Ukraine E-mail: zhdanovav@ukr.net Backup: To the best of our knowledge, there is no ocular motility disorder (OMD)-specific quality of life (QoL) tool, OMD-specific scale or method for patient profiling during treatment. Purpose: To develop an OMD-specific QoL assessment method in an effort to objectify treatment outcomes and to perform patient profiling during treatment. Material and Methods: We retrospectively analyzed outcomes among 240 patients (109 women and 131 men; aged 18 to 78 years; mean age, 36 ± 4.2 years) with OMD who received inpatient treatment at the Romodanov Neurosurgery Institute between 2004 and 2016. Out of these patients, 108 underwent surgeries for ruptured saccular supraclinoid internal carotid artery aneurysm, 65 underwent tumor removal (including: acoustic neurinoma, n = 23; pituitary adenoma, n = 26; and meningioma, n = 16) and 67 were treated non-surgically for craniocerebral trauma. Rehabilitative treatment was done in all patients (in operated-on patients, it was done early after surgery). Results and Discussion: We developed OMD-specific score assessment method and QoL scale involving a number of indices related to neurological symptoms, as well as to physical, psychic and social status of patients. A total OMD-specific QoL score of 0–15 is considered a poor (or low) QoL; 16–30, a moderate (or good) QoL; and 31–45, a high QoL. Not only the extent of damage to cranial nerves III, IV, and VI, but also the impact of physical handicap on the patient’s activities and on his functional abilities is assessed. Conclusion: Application of the OMD-specific QoL assessment method involving the QoL scale in clinical practice makes it possible to objectify treatment outcomes and facilitates patient profiling during treatment. Key words: rehabilitative treatment, ocular motility disorders, paralytical strabismus, quality of life Paralytic strabismus (PS) occurs after injury to nuclei and trunks of cranial nerves III, IV, and VI, as well as after injury to extraocular muscles and their nerves. Cranial nerve injuries and resulting ocular motility disorders (OMD) are common in neurological and neurosurgical patients with craniocerebral trauma, vascular disorders, brain tumors, and central nervous system inflammation [1-6]. In these cases, management of PS involves therapy of the underlying disorder, as well as combination treatment (including electric neuromuscular stimulation, other physiotherapeutics, and therapeutic physical training). One cannot express the limitations in home and social activities caused by PS using well known physical units. This calls for the development of a disease-specific instrument (a test, a questionnaire or a scoring system) to assess not only the extent of pathological changes, but also the above mentioned limitations in PS. Specific quality of life (QoL) assessment methods and treatment outcome profile tools are already used in craniocerebral trauma, stroke and cerebral vascular disorders, as well as spinal injuries, making it possible to collect data on the functional status of patients with a variety of neurological manifestations in order to assess muscle spasticity, tone and strength, pain level, local functional abnormalities (e.g., those of hand function), etc [7-8]. To the best of our knowledge, there is no OMD-specific QoL assessment method or scale that can be used as a QoL assessment and treatment outcome profile tool for patients with dysfunction of cranial nerves III, IV, and VI. The study purpose was to develop a comprehensive OMD-specific QoL assessment method involving the indices related to neurological and ophthalmological symptoms, as well as to physical, psychic and social status of patients. Materials and Methods We retrospectively analyzed outcomes among 240 patients (109 women and 131 men; aged 18 to 78 years; mean age, 36 ± 4.2 years) with OMD who received inpatient treatment at the Romodanov Neurosurgery Institute between 2004 and 2016. Out of these patients, 108 underwent surgeries for ruptured saccular supraclinoid internal carotid artery aneurysm, 65 underwent tumor removal (including: acoustic neurinoma, n = 23; pituitary adenoma, n = 26; and meningioma, n = 16) and 67 were treated non-surgically for craniocerebral trauma. Rehabilitative treatment was done in all patients (in operated-on patients, it was done early after surgery). We developed OMD-specific scoring method and QoL scale (involving a selected number of OMD-specific indices related to neurological symptoms, as well as to physical, psychic and social status of patients) using the Rehabilitation Activities Profile [9] and the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) [10] as prototypes. The Rehabilitation Activities Profile is a clinical assessment tool which can be used as a checklist with a 0-3 point severity rating. Besides the patient’s self-assessment, the NIHSS considers the assessment made by medical personnel [7-8]. The authors of this paper have been granted patent No.43940 “A technique to assess the quality of life in patients with ocular motility disorders” in Ukraine [11]. Results Patients and medical personnel (doctors) had been asked to answer the questions of the QoL Scale prior to, just after and 2-3 months following rehabilitative treatment. Points were assigned to each item, total scores were calculated, and post-treatment total scores were compared with pretreatment total scores. The QoL scale has two subscales, subscale A (15 questions with each question having three possible responses) and subscale B (5 questions with each question having four possible responses), with the questions answered by the patient and the doctor, respectively. As per WHO guidelines, the patient’s status assessment is based on not only the intensity of pathological process but also influence of the disease or of the trauma on the patient’s self-care ability, home and social activities. Comparison of physician's assessment scores with patient-reported scores makes it possible to deepen understanding of the functional handicap and of the patient’s adaptation to this condition. With the testing completed, total scores are calculated. A total OMD-special QOL score of 0–15 is considered a poor (or low) QoL; 16–30, a moderate (or good) QoL; and 31–45, a high QoL. OMD-specific assessment of treatment outcomes and QoL over time is performed by comparison of total pre-treatment and post-treatment scores. Not only the extent of damage to cranial nerves III, IV, and VI, but also the impact of physical handicap on the patient’s activities and on his functional abilities is assessed. The extent of neurological manifestations and the patient’s QoL are identified at different time points. Example Ms. O.P. M-k, aged 29 years, was operated for left cerebellopontine angle neurinoma. Postoperatively, a left cranial nerve VI palsy was observed. A paralytic esotropia was present, with a left eye turned inward, and no eye movements outward, toward the central axis and away from the central axis. Soon after operation, the patient was discharged from the inpatient unit for family reasons. Her neurological symptoms persisted, and, 2 months later, she came back to the unit to undergo a course of rehabilitative therapy for OMD. The patient and the doctor were asked to answer the questions of the QoL Scale prior to treatment (i.e., at baseline). The patient’s baseline present total QOL score was 8, reflecting “poor” (or low) QoL. After she underwent the course of rehabilitative therapy for OMD, positive ocular motility changes were observed in her left eye, and eye movements (outward, toward the central axis and away from the central axis) were restored. The patient was re-examined, and her QoL was re-assessed with the QoL Scale. Just after the course of rehabilitative therapy for OMD, the patient’s total QOL score was 27, reflecting “good” (or moderate) QoL. During the follow-up, she maintained the positive functional changes. At the 3 month follow-up visit, the function of the specific nerve was restored completely, and the patient had no OMD-related complaints. She was re-examined, and her QoL was re-assessed with the QoL Scale. Three months after the course of rehabilitative therapy for OMD, the patient’s total QOL score was 44, reflecting “high” QoL.

Conclusion Application of the OMD-specific QoL assessment method involving the QoL scale in clinical practice makes it possible to objectify treatment outcomes and facilitates patient profiling during treatment. References 1. Gusev EI, Konovalov AN, Burd GS. [Neurology and Neurosurgery]. Moscow: Meditsina; 2000. 656 p. Russian 2. Carlsson J, Rosenhall U. Oculomotor disturbances in patients with tension headache treated with acupuncture or physiotherapy. Cephalalgia. 1990 Jun;10(3):123-9. 3. Heitger MH, Anderson TJ, Jones RD. Eye movement and visuomotor arm movement deficits following mild closed head injury. Brain. 2004 Mar;127(Pt 3):575-90. 4. Kraus MF, Little DM, Donnell AJ et al. Oculomotor function in chronic traumatic brain injury. Cogn Behav Neurol. 2007 Sep;20(3):170-8. 5. Kraus MF. The role of oculomotor function in the assessment of traumatic brain injury. Brain. 2013 Apr;146:573-89. 6. Miller NR, Newman NJ: The Essentials: Walsh & Hoyt's Clinical Neuro-ophthalmology. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1999, pp 245-268. 7. Belova AN. [Neurorehabilitation: Manual for Physicians]. 2nd ed. Rev. and Exp. Moscow: Antidor; 2007. pp.404-10. Russian 8. Belova AN, Shepetova ON. [Scales, tests and questionnaires in medical rehabilitation]. Moscow: Antidor; 2002. 440p. Russian 9. Van Bennekom CA, Jelles F, Lankhorst GJ. Rehabilitation Activities Profile: the ICIDH as a framework for a problem-oriented assessment method in rehabilitation medicine. Disabil Rehabil. 1995 Apr-Jun;17(3-4):169-75. 10. Brott T, Adams HP Jr, Olinger CP, et al. Measurements of acute cerebral infarction: a clinical examination scale. Stroke. 1989 Jul;20(7):864-70. 11. Zhdanova VM, Zadoianyi LV, Tsymbaliuk VI. [Patent for useful model No. 43490 MPK A61V8/10, “Method for quality of life assessment in ocular motility disorders”]. 2009. [Patent Bulletin No. 16]. Ukrainian 12. Golovin SS. [Clinical Ophthalmology]. Vol.1, Moscow: Moscow Publishing House; 1923. p. 335 13. Avetisov ES. [Concomitant strabismus]. Moscow: Meditsina; 1997. pp. 158-9 Russian 14. Morozov VI, Iakovlev AI. [Visual pathway disorders: clinical picture, management and diagnosis]. Moscow: Binom; 2000. 165 p. Russian 15. Avetisov ES, Kovalevskii EI, Khvatova AV. [Manual of pediatric ophthalmology]. Moscow: Meditsina; 1987. 496p. Russian 16. Happe W. [Ophthalmology]. Transl. ed. Amerov AM. Moscow: MedPress-inform; 2004. 72-5 p. Russian 17. Katargina LA, editor. [Accommodation: Manual for Physicians]. Moscow: April; 2012. 136 p. Russian

|